By Matthias Feist

Some time ago, Michael asked me to write about my con preparation. I’ve been putting it off, unsure how to approach the topic, but I’ve finally found a way. I’ll take you through my preparation for Q-Con at Queen’s University Belfast, an event organized by the DragonSlayers Student Society for over 30 years. What started as a role-playing and board game convention has evolved into a vibrant and diverse weekend takeover of the university’s main grounds in June.

This is my second Q-Con, and an informal introduction to Star Trek Adventures I used last year for a group of players was well-received. Last year, I couldn’t offer an official game, but this year, working at the university, I made sure I was on the docket. I anticipate being the sole Star Trek Adventures Game Master at any convention, so I know I always need to bring my A-game.

For conventions, I use the pre-generated characters from the second edition rules. All sheets are laminated, and each player receives a stand-up with character art on the front and a summary of key momentum and determination rules on the back. Players can write their names and pronouns on the stand-ups, eliminating the need to remember everyone’s names. I’m building a small library of convention games, typically three to four hours long and self-contained, though they may reference existing Star Trek properties.

My design rules: familiarity, openness, accessibility, and playfulness

I have a few design rules for Star Trek Adventures games.

The first, and most crucial, is to create familiarity. Many players at the table may not have played Star Trek Adventures but are curious because they’ve always loved Star Trek. I aim to give them moments where they exclaim, “Wait, isn’t that so-and-so from that episode?” This can be a deep cut or a cameo from a well-known character. Perhaps it’s Nurse Chapel gifting Dr. Roger Korby’s notes to a character exploring the Orionic Empire, or we’re following up on a one-time villain from the original series.

My second principle is openness. My convention games must be enjoyable for someone who likes Star Wars but knows little about Star Trek. I want them to have a fun and engaging experience, even if they never play Star Trek Adventures again, so they’ll share stories and laughs about this single game with friends in the years to come. I use easily relatable points of reference, such as late 20th-century Earth history. For instance, my convention game “Where No Dog Has Gone Before” is about Laika, the space dog, from 1957. While my players may not recall the Cold War as vividly as I do, they’ll grasp the concept, and if they research it later on Wikipedia, they’ll find the story thoroughly researched and historically grounded.

My third principle is accessibility. I constantly learn new things about this during my games. One lesson is to provide large print versions of character sheets or bring my LED magnifying glasses, as some players may have difficulty reading A4 10-font printed character sheets. I also observe and listen for cues regarding noise sensitivity, including music, to ensure neurodiverse players feel welcome. As a GM, I provide standees for characters and ask players to write their pronouns on them, setting an example by including my own. I might wear my rainbow lanyard or a small button to signify that I am an LGBTQ+ ally.

Most conventions I’ve been to have been highly diverse, much more concentrated than even daily university life. Q-Con is probably the strongest in this regard. That’s a credit to the DragonSlayers society.

My fourth principle is being playful during the design process. I use the Captain’s Log solo roles to create and play out the storyline. It helps me gauge the difficulty of the scenario and fill in character backstories. Major NPCs’ recent history may be played out to give them more depth, but also to work out potential kinks in the storyline. The rules are great to explore different ways to solve (or create) complications and challenges for the players. I also tend to run the storyline with the pre gen characters in advance, so I understand the potential game flow and avoid bottlenecks or points of disorientation for the players.

Q-Con Day 0.5: Pre-Convention Warm-up

I wanted to ensure I was fully prepared for Q-Con, so I offered to run a Star Trek Adventures game at the Student Union-run Reboot Gaming Cafe.

I knew building an audience for Star Trek Adventures would be a grassroots effort.

I knew this would be challenging, as the usual reaction to a Star Trek role-playing game in such settings is often a surprised “Oh, no D&D?!” I anticipated a small, not tough, crowd.

To their credit, the people at Reboot Belfast are amazing; they were very supportive, providing a table and promoting the session on their Discord. One player expressed interest on Discord, and one player showed up. I wasn’t disappointed or surprised; I knew building an audience for Star Trek Adventures would be a grassroots effort.

I decided to run “The Celestial Algorithm” from the quick start guide. I volunteered as a GM at the UK Games Expo last year and, after signing an NDA, ran the game with modifications there. So, I know the scenario well enough to run it even under challenging circumstances.

Could we run the scenario with just one person, playing all the individual characters of the USS Challenger? Yes, we could! Credit goes to ‘S’ for their amazing work. They had never played Star Trek Adventures before but took to it like a fish to water.

In a joyous session of just under three hours, they played the adventure from the perspective of Security Officer Xanx, regularly embodying other characters as needed by the scene.

I’ve always enjoyed playing “The Celestial Algorithm” with a strong focus on the environmentalist Orion storyline. This provided some of the most hilarious moments, creating traits about difficult working relationships under pressure and people recognizing that working together is the essence of Star Trek Adventures, despite their preconceptions and different ideologies.

I noticed two women playing a board game at another table, glancing over throughout the session. After my game finished, they approached, and one, a big Star Trek fan, asked all sorts of questions about how Star Trek Adventures differs from Dungeons & Dragons—a common reference point. I was happy to explain how the mechanics are more forgiving when a dice roll goes wrong, eliminating the frustration of waiting 15 minutes only to roll badly again, and how the game encourages creativity when jointly creating complications and traits.

Not to forget the strong drive to play collaboratively.

So, one player has become three!

The team from the store, who had been promoting the game and raising awareness while it was underway, were delighted to hear I might now have three players. We’re even discussing a potential monthly Star Trek Adventures game at the cafe! And this is all before Q-Con even began!

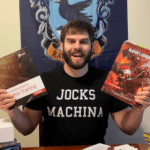

I heavily promoted my convention sessions, and I’m writing this on the morning before my first game. I’ll be playing my convention workhorse mission brief, “All Out of Bubble Gum.” My bag is packed, and this on-person Star Trek Adventures promotion machine is ready to rumble!

Q-Con: The Convention Itself

Q-Con is a delight. Over the entire weekend, the main campus is taken over by what appears to be a couple of thousand cosplayers. This student-organized event has been running for over 30 years.

Like all student-run events, it’ll always be a bit messy – but it isn’t corporate, and that makes part of its charm. At any conventions I go to, I consistently seem to be the only Star Trek Adventures Game Master. While this is somewhat sad, it’s also beneficial as I get first dibs on all those Star Trek-curious players. And indeed, they came.

On Saturday, I had four players, and on Sunday, I had seven. Word had spread, and one of the Saturday players attended both games. This is why I offer two different scenarios at conventions; it gives players who enjoyed the first session a second chance and that helps me attract more players.

When players arrive, they can choose from the character sheets and standees. I give them a small green token symbolizing determination. I always begin by asking about their relationship to Star Trek, their role-playing experience, and if they’ve ever played Star Trek before. I’m most excited when I get a mix of everything. More than once, I’ve had couples or families where one person might be reluctantly dragged along. I always make sure to give the potentially more skeptical party special attention and encourage them to “just do it.”

I explain the mechanics of dice rolling, Momentum and Threat, Determination, Values, Talents, and Focuses. I have summaries of key concepts on the backs of the character sheets and standees, and often, players who know the mechanics (some will have played other 2d20 games) will help out, which I encourage. I ensure that players can do everything in the game based on the assets I’ve given them, which usually include a briefing sheet about the planet they are visiting or a piece of evidence revealed during their investigations.

As in my regular games, I go very light on combat. I emphasize the collaborative elements of the game, explaining how they are built into the rules and how this makes it feel like Star Trek. I prefer whimsical scenarios or those with small to medium stakes. Saving the universe is not on the menu; saving an innocent dog sent into space in 1957 is. I write the scenarios in the format of mission briefs, firstly to ensure they can be solved in three-plus hours, and secondly, because I intend to publish them to the community eventually.

I want players to feel seen, smart, and competent, to feel good about themselves.

I try to make all stories relevant to our modern or at least recent history. This primarily engages non-Star Trek players who might struggle to orient themselves in this strange new world. Expect modern references, memes and jokes, famous quotes, and of course, plenty of genre references. I always enjoy when players start recognizing these references, making them feel good about the shared inside joke, or when some of them suddenly, mid-game, look at the briefing paper again and have a “Eureka!” moment. I want players to feel seen, smart, and competent, to feel good about themselves. For me, Star Trek sings when it’s relevant to our current moment, comments on the Zeitgeist, or simply makes us feel good about the potential future we could all share.

I want them to come back, to tell their friends about this amazing game, and to know there’s a space for them at our shared table. The greatest joy I get now from those who only ever have played the big dragon game, It’s great to see people come around to play in a different collaborative and more emotionally affirming way. No monsters on my table. And I always hope that they will remember playing Star Trek Adventures together.